Olivia Chow entered the Toronto mayoralty race as the acknowledged front-runner, the only left-wing candidate running against no fewer than four candidates from the right (John Tory, Rob Ford, John David Soknacki and, before she dropped out, Karen Stintz). Chow has star power (as the widow of the late Jack Layton), obvious outreach to visible minorities (who, collectively, are close to being the majority of voters in Toronto), recently had her biography published by Harpercollins, and is well-known to voters in Toronto thanks to her years of service as a city councillor.

According to a string of recent polls, she is now running in third place, behind Rob Ford, a man so demonstrably unfit for office that many of his own supporters would be mortified were they to discover that he had become, say, the principal of their child’s school.

To say that something had gone wrong with Chow’s campaign would be an understatement. At the same time, there have been no dirty tricks, no vicious smears, no negative tactics. The problem is not even with the candidate (although she’s not a very effective public speaker). The real problem is with her politics. And that is why the failure of her campaign carries with it lessons for the left across Canada, not just in Toronto.

The problem with Chow, to put it bluntly, is that she is too left-wing. She is also more ideologically rigid than Jack Layton (not to mention much more earnest), and so is incapable of coming across as anything other than ideologically left-wing. As a result, she has very little appeal outside of the traditional NDP base of what I like to think of as “genuinely left-wing voters,” who make up about 20% of the electorate in Canada – slightly more in downtown Toronto, slightly less in the near suburbs.

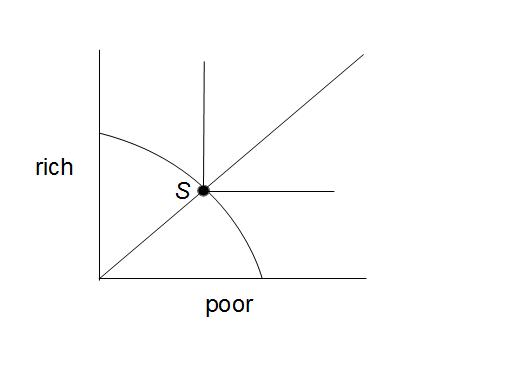

I want to explain briefly what I mean by “genuinely left-wing,” because some people have doubts as to the usefulness of these labels. My own view is that the left-wing/right-wing vocabulary is extremely useful for thinking about fundamental attitudes people have toward the role of government, especially right now in Ontario, where there are very clear ideological differences between the various political parties (as I have written about here). In the background of my thinking is a very simple little picture, which I use to mentally locate and classify the positions of various candidates on basic “political economy” questions.

Bear with me for a bit, the picture really is quite simple, bordering on simplistic, but it takes a little bit of explaining to see what everything represents.

The graph represents the division of the social product between two classes of society, which I’ll call the “rich” and the “poor” (you could add more classes by adding more dimensions, but in order to make it easy to draw here I’ll just make it two). The point S is the status quo, which represents how things are right now, involving a certain quantity of benefit, along with a division of that benefit between the two classes. The curve that it is sitting on is something like the “production possibilities frontier,” which constitutes the set of different distributions of the benefits that the state could be producing with the resources it has. Old hands will recognize the points to the north-east of the status quo as the set of Pareto improvements, which is to say, changes that make everyone better off.

Now, take an issue like transit, which is on the top of everyone’s mind right now in Toronto. No candidate favours the status quo. But where they want to move things is quite different, depending on the candidate. I like to think of there being four basic “zones” that people might want to move into (which I’ve coloured in below). For the sake of discussion here I’m ignoring the set of changes that make everyone worse off, although those are not without their advocates.

I take it that anyone who wants to move things in the direction of greater equality (i.e. favouring the poor) is “left,” which in my little picture means favouring outcomes that are below the ray that I’ve drawn between the status quo and the origin, and to the right of the status quo. These represent the set of changes that make the poor better off, relatively speaking. The “right” is just the mirror image. I then distinguish between “centrist” and “hard” versions of left and right-wing ideology, based on whether that person is willing to countenance purely redistributive transfers.

What I think of as “centre-left” positions are those that want to increase the social product (i.e. shift the possibilities frontier outward), but do so in a way that is more advantageous for the poor than for the rich. Typically this means that the person wants to provide some sort of public good, paid for by taxes that are progressive with respect to income. Wanting to increase property taxes to build public transit would be an obvious example. It makes everyone better off, but the net benefit to the poor is greater.

“Centre-right” positions, by contrast, also want to use the power of the state to expand the possibilities frontier, the difference is that they want to do so in a way that favours the rich rather than the poor. Typically this involves solving some sort of collective action problem, but doing so in a way that relies upon the market pattern of income distribution to establish access. (The whole “favouring the rich” part need not be read pejoratively, typically it doesn’t involve showing favour to the rich, it just means deferring to market patterns of distribution, which are less egalitarian than the pattern established through state taxation-and-provision schemes.) Road tolls to reduce congestion would be an example of a classic “centre right” position – it clearly expands the possibilities frontier, generating a benefit for everyone (reduced travel times), but it regulates access to that benefit through willingness to pay.

As far as my own political proclivities go, I am firmly in this centrist category. I lean somewhat to the left, based largely on a sentimental awareness of the fundamental unfairness of life and the extent to which my own privileges are unearned. At the same time, my antipathy toward unresolved collective action problems is so great that I am happy to embrace centre-right proposals when nothing else seems better (e.g. road tolls, carbon taxes).

As a result, the two positions that I find most exotic are the ones that I’ve labelled here as “hard left” and “hard right,” but which might also be described, less tendentiously, as just “genuine left” and “genuine right.” What characterizes these views is that they are both to some degree non-welfarist, which is to say, they assign a sufficiently great value to a particular political principle that they are willing to make one or more person worse off, in terms of welfare, in order to achieve it. Typically “equality” is the principle that plays this role for the left, while “liberty” plays this role for the right.

According to these “hard” views, government is fundamentally not about “solving problems” or enhancing social welfare. From the right-wing perspective, it is about a struggle between the individual and the state, with the state constantly trying to limit the individual’s freedom. So, for example, the hard-right ideologue is opposed to taxes in principle, on the grounds that they are coercive, regardless of what public goods they are used to provide. Wanting to eliminate government services, in order to reduce taxes, is therefore typically a hard-right position. (In this sense, the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, and quite often the Fraser Institute, are hard right, because they constantly complain about the absolute level of taxation, while ignoring entirely the social welfare benefits that come from government spending – this is akin to complaining about the price of beer, without considering how large the glass is, a position that would only make sense if one thought that, in principle, people should not have to pay for beer.)

With respect to transit, the concern for individual liberty shows up as a preference for cars, on the grounds that “personal vehicles” both reflect and promote individual freedom. Mass transit, or more accurately, collective transit, is from this perspective an attempt to limit and control the autonomy of the individual. People who think this way – and there are a lot more of them than many downtown liberals like to imagine – would rather suffer through congestion, in order to preserve the privacy and freedom that come with driving their own car. So the hard-right politician (e.g. Tim Hudak in the last provincial election) wants to shift spending away from public transit toward highways.

And finally we get to “hard left” positions. With the centre-left, distributive justice questions get relegated to a secondary status, having to do with the terms under which collective benefits will be produced. To the hard-left ideologue, by contrast, distributive justice considerations move to the forefront, while the concern about collective benefits becomes secondary. From this perspective, the fundamental mission of government is to correct the inequality of market outcomes, by taking money away from the rich and, in various ways, giving it to the poor.

Now I guess my centrist tendencies are so strong that, when it comes to transit in Toronto, it hadn’t even occurred to me that there was a hard left position to be had. It just seemed that congestion in the city is so obviously a collective action problem, that any proposal would have to constitute some sort of a general improvement over the status quo. And yet Chow managed to find a position that is firmly in what I’ve indicated as “hard left” territory. She says that her number one priority is to improve buses and bus service. Because buses are how the “most disadvantaged” get around.

And it’s true. In general people like subways – mainly because you don’t have to wait outside for them in the winter. So wherever you build a subway, people want to live nearby. As a result, neighbouring property values go up. This in turn displaces the poor, who then wind up in neighbourhoods that are only served by buses. So according to Chow, we should be taking some of the money that is earmarked for spending on subways and redirect it to bus service, which generates a greater benefit for the poor.

This is nice and everything, but as a campaign issue it’s not exactly a vote-getter. The problem is that Chow is thinking about the whole transit issue in distributive justice terms. In her mind, it’s all about taking a “progressive” policy position. And being progressive, in her view, involve promoting social justice. As far as social justice is concerned, she subscribes to what Alan Wolfe once called the “reverse Thrasymachus view,” namely, that “justice is the interest of the weaker,” which in this case means “helping the poor.”

In a way, her view of public transit is like a mirror-image of a certain right-wing view. Many conservatives dislike public transit because they think that it’s basically for poor people, and so see it as an extension of the welfare system. It’s a handout to people who can’t afford a car. They don’t see it in collective action terms (e.g. how to transport 500,000 people to work in downtown Toronto every morning). Similarly, Chow doesn’t see it as a collective action issue, she sees it in the same distributive justice terms as the conservative, but with the valence of the moral judgement reversed.

The problem with Chow’s position is that, for the average voter, she is making a pitch that relies for its appeal entirely upon the voter’s moral concern for the welfare of others. She has not announced any major policies that will improve the welfare of the median voter. Her pitch is not “vote for me, and I’ll make your life better,” it’s “vote for me, and I’ll make you feel better, by making some poor person’s life better.” Now I don’t want to dispute the moral sentiment here, I just want to suggest that appealing to people’s altruism does not provide a very strong basis for building an electoral majority.

In case anyone thinks her problem is confined to the transit file, here is another example. After a series of polls showing her lead evaporating, she decided to do a media event focused on a major policy announcement. She then announced a commitment to increasing land transfer taxes on very expensive homes, in order to provide subsidized school lunches that will benefit 36,000 children across the city.

This is nice and everything, but it’s important to see that, as a policy, it is firmly in the orange box. And it flies right over the head, or under the feet, of practically the entire electorate (since the tax affects maybe the top 10% of Toronto residents, and benefits only those among the bottom 10%, while leaving the vast majority of the electorate unaffected). What is crucial about this policy is that, in order to care about it, you have to take a moral interest in the welfare of these children.

Meanwhile, the condition of public schools across the board in Toronto is a complete mess. For example, over the past decade, something like 200,000 new condo units have been built south of Queen St., and not one single new school. Condo developments even have giant signs out front with a legal notice on it that says, basically, “you can move here, but be advised that there are no schools.” The city seems to be taking a gigantic gamble that, because the units are so small, people will move out when they have kids. This is looking, to an increasing degree, like a bad gamble (something that should be obvious to anyone who has travelled around the world a bit – people live in small apartments with kids all over, there’s no reason that Canadians can’t). So there are a lot of investments that could be made in the public school system that would have very broad appeal. But instead of focusing on these issues, Chow instead wants to create a lunch program for the poor.

Again, there’s nothing wrong with a lunch program. It’s just that you don’t win elections by promising to give other people free lunches. For the average person, life in Toronto sucks in innumerable ways. Traffic is a nightmare, public transit is crappy and overpriced, housing is too expensive, air quality is terrible, schools are underfunded and there is practically no busing, programs are oversubscribed, daycares are all full, you have to shovel your own snow, and it’s practically impossible to get out of town on weekends. If you want to become the mayor, you need to be able to say to the average voter, “this is how I’m going to make your life suck a bit less.” And at the end of a four year term, you need to be able to say “this is how I made your life better.” If you can’t, people will get angry, and will elect someone like Rob Ford, who at least promises to cut their taxes.

Seems to me you really ought to introduce yet another gradation. Many positions on what you’d represent as “hard” left, and even a few on the “hard” right (although much fewer given the relative numbers of rich and poor) actually increase utility even though they’re not “Pareto efficient”. After all, your “centre left/right” span only includes solutions or positions that make nobody worse off overall. I’ll leave aside the point that there are actually hardly any solutions to any public policy question that genuinely meet that qualification.

The point is, outside the “Pareto efficient” zone where it is not the case that even one person is worse off, you can very well have solutions that make, say, one person worse off and a thousand people better off. You can even(both in theory and, quite often, in practice) have solutions whose net benefit is greater than any of the Pareto-efficient ones. In practice I say, because in practice most solutions to any given problem that aren’t half- or quarter-measures, will make somebody worse off. So if you want to do something very useful overall, you’re generally going to have to gore somebody’s ox.

I’d want to argue that there is a distinction between a (leftist or, hypothetically, rightist) who will only advocate non-Pareto-efficient outcomes if the benefit is solidly greater than the penalty, and an ideologue who will advocate in favour of their “side” (the poor or the rich) even if the net outcome is negative, with penalties to more people than benefit.

Again, in practice, this forms the major distinction between “hard” left and right which makes something of a mockery of nice evenly split graphs like yours: Most “hard” leftists, whether on purpose or simply as a by-product of advocating for the larger group, push solutions which, while they will disadvantage the rich, will advantage the poor a lot more both in numbers affected and average change in utility. Whereas most hard rightists push for policies which benefit a relatively small number of people and give them only positional goods, at the expense of creating very considerable quality of life problems for quite large numbers of people, or even causing large numbers of premature deaths.

None of this touches the analysis of Chow’s politics and optics, which I can’t really speak to.

It’s an interesting argument. I’m not sure to what extent it explains Chow’s policies, but I tend to agree that if she’d made infrastructure improvements – transit expansion, better service, schools, parks, etc – the centrepiece of a broader platform she might still be winning this. I don’t really understand why she didn’t do that, especially since Tory’s plan represents both a flipflop on the DRL and an untenable fiscal plan.

Here’s a much simpler analysis: the NDP just doesn’t have very good strategists.

The Chow campaign adds one more data point to the recent elections in BC, ON, and NS, plus the loss (or near-loss) of byelections in Trinity-Spadina, and earlier, in Victoria.

From out on the west coast, it’s hard to know in detail what’s going on in Toronto. But I note that some local observers don’t see Chow’s problem as one of excessive leftism: https://storify.com/karengeier/dear-olivia-chow

The NDP seems to be using these recent campaigns as iterative attempts to perfect a consistently losing formula: simulate squishy centrism just enough to demotivate traditional supporters, but not convincingly enough to attract wavering (L)(l)iberals.

Funny that you got “Soknacki” right but “David” wrong.