I notice that Dr. Danielle Martin is going to be giving a talk on Monday (May 12) on campus here at the University of Toronto, so to celebrate the occasion I thought I’d discuss Canadian health care for a bit.

Incidentally, for those who don’t follow these things, Dr. Martin recently quickened the pulse of Canadian nationalists everywhere by smacking down a Republican Senator on television:

This video quickly came to occupy a place in the policy wonk’s heart, like an understated version of the “Joe Canadian” rant. (For those of you who missed that one, see here:

One cannot help but be impressed by her poise and self-confidence as she challenges his talking points. At the same time, people familiar with the state of affairs in Canada may have cringed a bit during the discussion of wait times. Because while the Canadian health care system performs very well in certain dimensions, in the area of wait times we are an international underperformer.

For example, in the little series that vox.com recently ran on single-payer systems, this chart caught my eye:

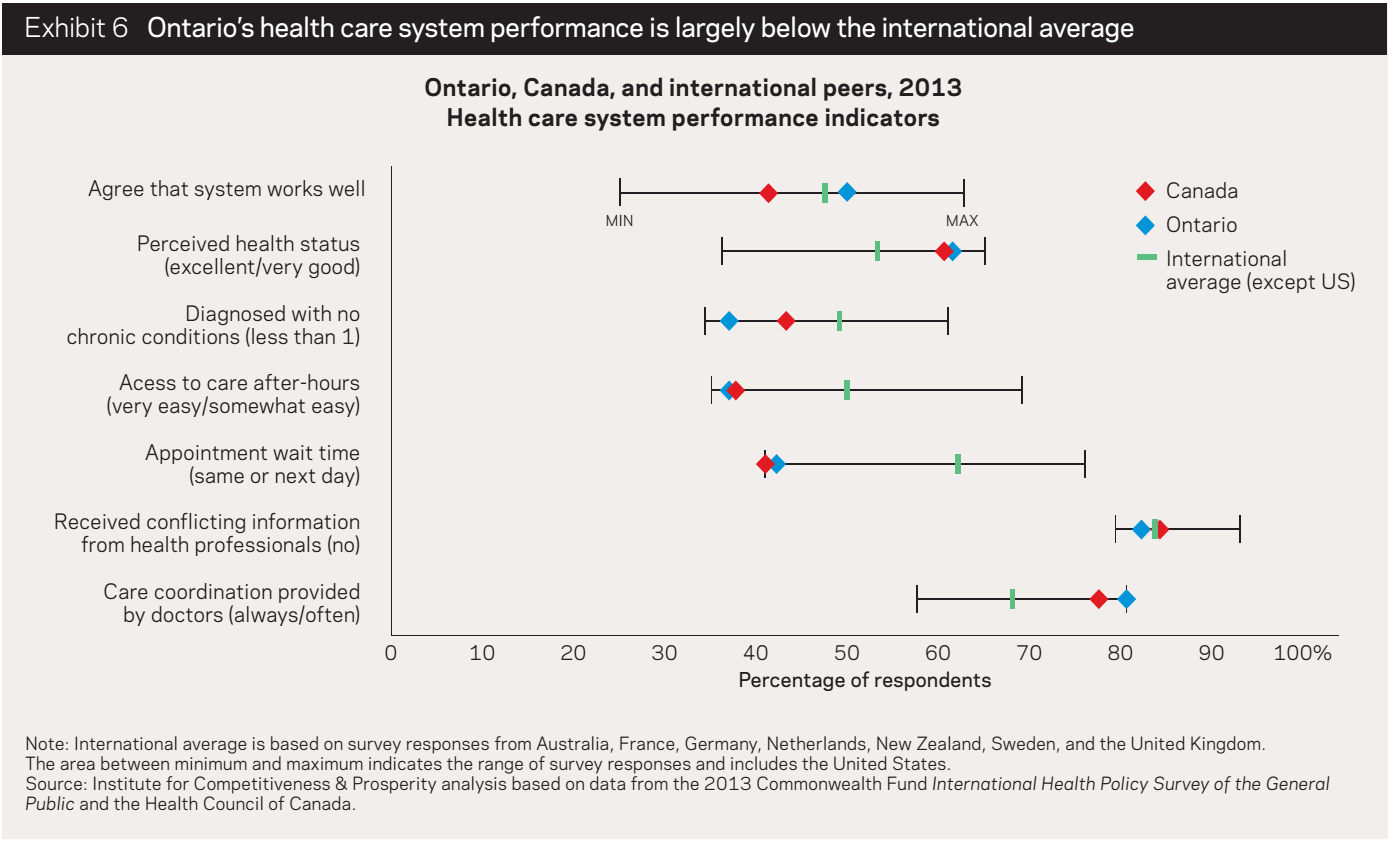

Or if one looks at the excellent working paper released by the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity on health care in Ontario, one can find this disturbing exhibit (item 5):

Overall, the performance of the Canadian health care system with respect to wait times is brutal. (Incidentally, the data above is for Ontario – a province that is far above the Canadian average, in terms of how many residents say the system “works well” [item 1].)

It is amazing that, as the situation has continued to deteriorate, the issue of wait times has almost disappeared from the national agenda. This is an illustration of the many ways that politics can punish the virtuous and rewards the wicked. By trying to actually do something about wait times, Paul Martin wound up giving the issue significant profile, which hurt him in the end, because there was no quick fix for the problem. By ignoring the issue entirely, Stephen Harper has managed to make the issue disappear from the national consciousness. (Although it should be noted that this is part strategy, but part also political ideology. Since health care is a provincial responsibility, he has a principled commitment to the view that it is simply none of the federal government’s business how long wait times are.)

In any case, one might wonder why wait times are such a problem in Canada. One might also wonder why pundits are always claiming that “throwing money at the problem” will not make it go away. Why not? After all, if you’ve got too many people standing in line at the grocery store, an attentive manager need only send out another cashier to reduce line-ups. And if there aren’t enough cashiers around, the manager need only go out and hire some more. So why not the same with health care?

The pundits are largely right, that this sort of approach will not work for health care (although at a certain point throwing money would no doubt solve the problem, but no one is willing to throw the amount of money that would be required). The major reason is that there is no such thing as “the manager,” in the Canadian health care system. This tends to be obscured by all the talk about “socialized medicine,” and the idea that health care in Canada is in “the public sector.” This is the biggest, most important point, that most Canadians don’t get, and that makes it really difficult to have a public discussion about health care in Canada. We do not have government health care, we have government health insurance. Most care is delivered privately. When you call up you doctor’s office, the person you are speaking to is an employee of a private, for-profit firm, owned and operated by the doctor (or perhaps a group of doctors). And when you go to a hospital, you are usually dealing with a private non-profit firm (just like you would be in the United States.)

The basic problem with private medicine is not that markets for care do not work properly, it is that markets for private health insurance do not work properly. In America, the fact that insurance markets have been failing for decades has meant that there has been significant innovation in the way that care is delivered. In particular, health providers, like HMOs, have stepped into the breach, and begun to provide a lot of insurance-like services. In Canada, none of that has happened. Because the government intervened so decisively in the insurance market, and essentially solved the fundamental problems of health insurance in the country, health care provision could continue along unchanged. As a result, the way that health care in Canada is delivered is much more like an old-fashioned, 1970s-style market system, with a whole bunch of little mom-and-pop operations providing retail-level health care, then sending the bill to an insurance company (which happens to be the provincial government).

In fact, the Canadian health care system relies so heavily on private incentives to deliver health care that it is sometimes referred to, in Europe, as a quasi-market system.

So what does this have to do with wait times? It matters because, first and foremost, the government has no idea what the wait times are for various procedures. That’s because there is no central list, or queue. Every single doctor keeps his or her own list. Suppose you have cancer, and your GP refers you to a surgeon or an oncologist for treatment. How long do you wait? That depends on many things. Most importantly, it depends on who your GP refers you do. There is no central database or source of information for referrals. GPs tend to deal with certain specialists, largely based on personal relationships they have cultivated over time. So a particular GP will refer her patients to Doctor X for colonoscopies, Doctor Y for mammograms, and so forth. At the time that she makes the referral, she typically has no idea how long you will have to wait, to get your colonoscopy or mammogram. Doctor X might have a huge wait list, so it will be 3 months before you can get an appointment. Meanwhile, there could be another Doctor Z, with an office right next door to Doctor X, who has no wait list at all. But your doctor has no way of knowing this, and neither do you, because there is nowhere to obtain this information (short of getting on the phone and calling around to see where you can get the earlier appointment – which typically doctors won’t do, because it’s time-consuming and they don’t get paid to do it).

Now it should be obvious that if doctors don’t even know who’s got a big wait list and who doesn’t, the government certainly has no idea. The government doesn’t know because all of this is essentially going on in the private sector, without any state involvement (other than the fact that the state will, eventually, pay the bill). The government also has essentially no IT infrastructure, and so is at pains to figure out even how long the wait lists were several years ago, for a given procedure, much less how long they are at any given moment.

This is what Martin was referring to, in the video, when she used the example of going through security, and seeing that one other security point had no line at all. That made the problem sound a bit easier than it is though, because you can see how long a lineup is just by looking. But with a doctor’s office, the only way to figure out the length of the queue is to call them up and ask. This is, in fact, what the government has been reduced to doing in some areas.

Once it becomes clear how private and decentralized the provision of health care is in Canada, it starts to become more clear why wait-time reduction is so difficult. And one can also see how the system generates perverse incentives. In order to reduce queues, you basically have to convince the doctors who are getting too many referrals to give some of these patients away. (“Convince” is the key word. You can’t make them do anything they don’t want to do.) This can be difficult, for several reasons. There is an obvious financial incentive not to do it – it’s like telling Futureshop that, if the crowds get too large, they should start sending customers away to Best Buy. There is also the fact that many doctors treat their wait lists as status symbols, and like to boast about how long it takes to get an appointment with them. So giving away patients not only reduces their own status, but unjustly increases that of their rivals. Doctors also use the length of their queues to negotiate for more resources (e.g. surgeons use the length of their queues to campaign for more OR time), so they have a perverse incentive to increase them.

Finally, there is a really subtle perversity, which is my personal favorite. If you ask a doctor who has a huge wait list to give away patients, they naturally have the freedom to pick and choose which ones to refer to their colleagues. Their natural inclination is to give away the most undesirable ones. There are a number of factors that can make a patient undesirable. Some patients are demented, or have difficult families, which makes them extremely taxing to deal with. Some patients have other complicating factors (e.g. chronic conditions like diabetes or obesity), which makes them much more work to treat, but which doctors cannot bill more for. So if you ask doctors to pass along some referrals to their peers, in order to reduce wait times, they will typically comb through their list and pick out all the worst ones. This makes the doctors on the receiving end extremely reluctant to accept patients “given away” by their colleagues. Some would rather sit around waiting for a clean referral than accept a “second hand” one.

Now it isn’t as though the government hasn’t been doing anything about this. One strategy has been to encourage doctors to form “practice groups” and to pool their referrals and patients, which tends to distribute resources out more equally. But you can’t make doctors do this, you can only bribe them into doing it – because they are mostly private, self-employed, independent providers. This is why politicians and policy types often talk about “buying reform” as their central strategy on wait-time reduction (whereas a naive observer might wonder why it wouldn’t be better to “order reform” and then “buy health care.”)

This no specific point to this, other than to describe how the system works – most people I talk to about this are shocked to discover how little central oversight and control there is. Most Canadians seem to assume that the Canadian health care system is like the British NHS, a giant vertically integrated state-owned health care bureaucracy, that keeps track of everything going on. It’s not like this at all. The big question is whether the chronic problems of the Canadian system can be fixed without creating something more like the NHS.

I did not appreciate how intractable this problem was. I assumed that if wait times were not increasing then the problem was not structural and throwing money at it would clear the backlog. This turns out to be a naïve view borne of a partial ignorance of how our health system actually works. Unfortunately, there also appears to be a bit of a catch-22 situation here: we can’t know the severity of the problem (other than by way of self-reported measures) without changing our system (to a more NHS-type model), but if we change to such a system we’ll only be measuring the efficiency of this new system, rather than the old one. In any event, it’s nice when debates about health care move beyond the “public” vs. “private” issue to a discussion of how to actually improve health delivery within a publicly insured model.