The leaves are starting to change colour, the morning air is becoming crisp. When fall arrives, a man’s thoughts naturally turn toward… hunting. Myself, being of a wonkier frame of mind, I tend to think less about hunting and more about gun control.

Unlike Americans, we Canadians are not burdened by the straightjacket of a centuries-old constitution, and so there is no entrenched right of gun ownership in our society. Furthermore, neither politicians nor the courts have seen fit to create one. Indeed, the Supreme Court Reference re Firearms Act was a pretty unambiguous smack-down to any sort of “rights” talk. The current federal government is about as gun-friendly as any we are ever likely to see.

Some people, however, seem to have missed the memo (he says, casting his eyes westward). For those who did miss it, I want to explain in simple terms why you do not have, and ought not have, any “right” to own a gun.

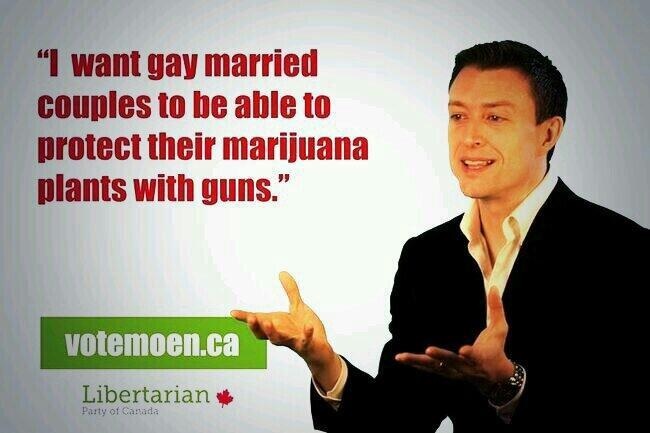

Speaking of missing the memo, I was struck by this advertisement that was making the rounds a while back, from a Libertarian Party candidate in a recent Alberta provincial election by-election.

This is worth a chuckle or two, but it is also gloriously confused. The folks in libertarian school don’t seem to be doing a very good job teaching people what the doctrine amounts to. Traditionally at least, libertarianism doesn’t mean “Everyone gets to do whatever the fuck they want.” That’s more like South Park libertarianism. Traditionally, libertarianism means “Everyone gets to do whatever they want, so long as it isn’t hurting anyone else.”

With this in mind, let’s look over that list again. Dope, gay sex, gun ownership… hmmmm. I don’t happen to indulge in any of these three, but you’re telling me that if you do, it’s absolutely none of my business, because it doesn’t affect me. None of these three things affects or harms anyone else, and so they fall within the realm of “individual liberty.”

Does that sound right? I don’t think so. I’m inclined to say that one of these things is not like the others…. Marijuana laws are paternalist. So are anti-gay laws. But guns? We’re supposed to believe that guns are a private, self-regarding choice? This is certainly not the standard argument. Gun control advocates are not saying, “you can’t have a gun, because you might hurt yourself.” The more usual argument is “you can’t have a gun, because you might hurt me” (cf. Reference re Firearms Act).

Let’s turn to our John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, the “classical liberal” view. On the classical liberal (i.e. libertarian) view, growing pot would fall within your rights because it doesn’t harm other people. So it’s nobody else’s business if you do it. Same with gay sex, it’s your own business. (Gay marriage is actually a bit trickier, since that’s a legal status, but we’ll let that one slide.)

Gun ownership, however, does harm other people. I know, because my neighbours own guns, and it harms me. The simpleminded response is to say “no it doesn’t, they would only be harming you if they shot you, which responsible, law-abiding gun owners (by definition) never do.” The argument then usually goes downhill from there, veering off into a discussion of statistics, and whether increased gun ownership increases the probability of me being shot.

I want to go in a different direction, and point out a more obvious fact, which is that a lot people are afraid of guns. You may not be, but I am. Guns scare the crap out of me. (I’m reminded of a story that an American friend of mine told me, the first time he held a Desert Eagle in his hand. “I was seized by a powerful feeling that nobody should own one of these,” he said.)

Also, people with guns scare the crap out of me. If you look at the public debate, you can tell that I’m not alone. Lots of people are, like me, genuinely afraid of guns. Not only that, we are genuinely afraid of people like you, who like to collect guns, shoot guns, and do whatever-else-it-is-you-do with guns. (And if you were honest with yourself, you would admit that part of the attraction of guns is precisely that other people are afraid of them. That’s why they’re so cool.)

So that is the harm of gun ownership – it creates fear in others. And limiting the ability of some to cause fear in others is a perfectly legitimate basis for legal regulation. After all, the major problem with street crime is not so much the actual damage that is done to persons and property (which is, in the grand scheme of things, not that large), it is the widespread fear that it causes.

Thus the only real question with guns is whether the fear they cause in others should count as a genuine harm. This depends on whether it is legitimate. For example, many people are also afraid of homosexuals – that’s why it’s called homophobia. Anyone who believes in gay rights must think that causing this fear in others does not count as a real harm – that the person who experiences this irrational fear should just get over it. Gun advocates say the same thing about firearms. The fact that guns cause fear is also irrational, and us wimps should just learn to get over it.

So this is the crux of the argument for the supposed “right” to bear arms. If it is reasonable for me to be afraid of guns, then that counts as an argument for controlling them. If it is unreasonable, then I should just get over it.

Some people respond by pointing to a rural/urban split on this. In the city, there is practically no legitimate use for a firearm, so owning one is intrinsically suspicious, and hence threatening. But is it so harmless in the country either? I’m not sure about that. Obviously if you’re in the middle of the wilderness who cares. But what about on a farm? Let’s examine the two cases:

Guns in the country

Even in the country, I would suggest that guns are neither awesome nor harmless. I would be inclined to classify them as a nuisance.

I own a farm that backs onto a conservation area, where hunting is allowed (because it’s such an important part of the “rural lifestyle”). It’s a nuisance. If I had to choose the number one thing that my neighbours do that reduces my quality of life, I would say it’s hunting. (The smell of manure, mailbox vandalism, barking dogs, Tim Hortons cups and Coors cans thrown out the car window, these are things I can live with. Guns are in a totally different category.)

I should mention, in this context, that several years ago my neighbour was shot dead by a hunter while walking her dog in the conservation area – not wounded, but shot dead. It led to a really noticeable decline in the number of people walking their dogs in the conservation area. I certainly don’t.

Lots of people hear this and shrug their shoulders, saying “She should have known better than to go walking in the woods during hunting season.” Okay, stop for a second listen to how that sounds. I’m not allowed to go walking in the woods anymore because you’re out there having fun (or communing with nature, or carrying on some important family tradition, or whatever), and who knows, you might just have an accident and shoot me dead.

Can you see how that makes you and your hobby a bit of a nuisance?

To make things worse, the fence between my land and the conservation area is not in great shape, and in some areas rusted out, so hunters are always wandering over onto my property. I bump into guys with shotguns and high-powered rifles in the forest on my land. The forest where my children play.

I don’t think it takes a huge leap of imagination to see how this could have a negative impact on my quality of life. It’s not the end of the world: we bought some blaze orange jackets and my wife got some blaze orange wool and knit scarves for the kids, which they wear from October until January. And for two weeks out of the year (deer hunting season) we don’t go into the woods at all (the woods on my land, I should note, my personal, private property, which some libertarians seem to think I should have a right to enjoy year-round).

Someday I’ll have to get the fence rebuilt, which will cost a couple thousand dollars. The only reason to do this is to keep the hunters off my land. That’s what I mean by “nuisance.”

So on the one hand, I get it when it comes to guns in the country. When I see a dozen wild turkeys slowly walking across my lawn, acting like they own the place, I’m also tempted to shoot myself some dinner. And when I come home to see footprints in the snow around the back of my house, I think about how long it would take the OPP to arrive if I needed them. At that same time, it’s important not to have any illusions. Widespread gun ownership, even in the country, can easily become a serious imposition on other people. That doesn’t mean you can’t have one, it just means that the terms under which you own one are going to have to be negotiated, and you’re going to have to expect to make some compromises. Just saying “it’s my right” doesn’t cut it.

And just saying “I’m sorry you had those experiences, but I didn’t do any of that stuff, and neither would any other responsible, law-abiding gun owner,” that also doesn’t cut it. I’m talking about what the real consequences are of having the laws that we have, and the way things work in the real world. In that real world, gun ownership, even in the country, can be a serious nuisance.

Guns in the city

In the city, there is practically no legitimate reason for owning a gun. That they are present at all creates an enormous amount of fear.

The standard response, from gun advocates, is to say that guns are no problem when they are in the hands of law-abiding citizens. It’s only in the hands of criminals that they cause problems – and why should responsible, law-abiding hobbyists be penalized for the actions of a few depraved criminals?

I just want to pause for a moment, and examine this concept – the “law abiding citizen” — that figures so prominently in all of these arguments. What does it mean to say that you are a law-abiding citizen? It means that, so far in your life, you claim to have respected all laws. Or at least the important ones. Maybe not the speed limit, or the one about smoking weed. Point is, you’ve never shot anyone, or robbed a store or anything.

What I want to emphasize is that, even if this is true, it is totally irrelevant. That’s because everyone is law-abiding until the day that they’re not. The nice old guy who shot and killed my neighbour was probably law-abiding as well, until the day that he shot and killed my neighbour (and in the end, he was acquitted of manslaughter charges, so I guess he remains law-abiding to this day). So you tell me that you are law-abiding? I could care less what you did in the past. Can you guarantee me that you’re going to continue to obey the law, for the rest of your life? No, I thought not. I’m just supposed to trust you.

What I don’t like, and what makes me afraid, is the fact that you have the ability to kill me on a whim. The fact that you say “don’t worry, I’m not going to do that,” doesn’t really make the underlying problem go away.

Consider the following, a little analogy that I cooked up.

Suppose that I have a peculiar hobby. I enjoy throwing rocks at little children and just missing them. I’m really good at it too, I’ve never hit one, I always just miss. I like to hang around at the neighbourhood playground, indulging my little hobby, picking up rocks, and throwing them so that they just miss hitting the kids who are playing there.

Naturally, this hobby freaks out the parents. “What are you doing?” they say, “stop throwing rocks at my kid!” I remain cool and nonchalant: “Relax lady, I haven’t done anything to your kid. I’ve been throwing rocks like this for 20 years, I’ve never hit a kid yet. Trust me.”

It’s obvious that my behaviour is seriously upsetting the parents of these children. Some of them are packing up and leaving the park. Others are pleading with me to stop doing what I’m doing. I go on about my business, gloriously ignoring all of the fear and suffering that my behaviour is causing. Why? Well when you think about it, it’s really the parents’ fault. If they could all just relax, there would be no problem. After all, I’m a responsible rock-thrower.

Does this sound like a reasonable defence of my actions? Probably not. One might be inclined to say that throwing rocks at children is just inherently dangerous, so that no matter how careful I am, or how responsible, the activity creates anxiety in others – and that this gives them legitimate grounds for regulating or controlling my behaviour.

Guns, I would submit, are also inherently dangerous. Their presence in a community creates fear and anxiety, no matter how responsible and law-abiding the owners.

Ultimately, what gun owners are saying to the rest of society is that we should all just trust you. In fact, you’re asking us to put an enormous amount of trust in you. But at the same time, you don’t seem to be showing a whole lot of concern for our feelings. In fact, you seem to be showing a callous disregard for the feelings of everyone but yourself. So how exactly are we supposed to trust you?

In fact, given the amount of fear that guns create, I have difficulty avoiding the sense that opponents of gun control lack a certain basic human decency. I mean, suppose that I really am a responsible rock-thrower, and it really is the case that I’m not going to hit any of the kids. Doesn’t the mere fact that I am upsetting the parents give me reason to take up some other hobby? Same thing goes for guns. To claim that others should live in genuine, mortal fear, so that you can enjoy your hobby, seems to me the essence of insensitivity. I don’t see any way to avoid the conclusion that, if you genuinely think this way, you are a bad person.

Academic post-script

Many people think that the inability to say anything helpful about the management of risk — cases where there is not yet any actual boundary-crossing, but only a potential one — is a serious limitation of libertarian theories. The canonical formulation of this objection can be found in Peter Railton’s paper, “Locke, Stock and Peril: Natural Property Rights, Pollution and Risk.” Since I don’t follow these things religiously, if anyone knows of any intelligent/cogent responses to the Railton piece, worth reading, please feel free to provide references.

Guns may make for a horrible hobby that fosters an environment of fear but private citizens are not the only gun owners, as long as racist, homophobic, corrupt and militarized police officers bear arms every citizen must live in the fear you rightly describe. If our police/government behave aggressively and violently it seems reasonable to allow private citizens to defend themselves from the military incursions of the state.

If I’m understanding this post correctly, the argument is meant as a philosophical one about the justifiability of restrictions on the use of firearms, and I think it makes a compelling case to that end. But I can’t help but think of what the policy implications of the argument might be, and for that we need to look at the empirical literature.

The clearest short assessment of that literature I’ve seen is this blog post (in French—sorry for those who can’t read it) by economist Vincent Geloso: http://blogues.journaldemontreal.com/libreechange/actualites/les-armes-a-feu-bien-ou-mal-aucune-idee/

Now the outcomes he looks at aren’t fatalities from gun-related accidents (which are what you mentioned in your post), but crime rates. According to Geloso, both concealed carry (which gun enthusiasts tout as a deterrent to crime) and gun control (championed by those on the other side) have little effect on crime rates. It turns out that crime is much more strongly related to factors that increase demand for guns (like drug prohibition, which makes it impossible to enforce contracts in the market for drugs except through (the threat of) violence) than to attempts to prohibit guns by law.

I don’t think Geloso’s has to be the final word on the issue, but it might be worth considering how your argument meshes with what we know from empirical studies to produce recommendations of policy.

In case anyone thinks that Joseph’s experience is an isolated case I can assure you it is not. As a farmer I owned a rifle but it’s use was restricted to shooting pests & putting the occasional sheep out of its misery. Hunting season coincided with the very time I needed to be in the woodlot bringing in winter fuel. But it was too dangerous. These “law abiding” hunters would trespass & hunt on my property without permission thereby breaking 2 laws both of which are unenforceable.

And to Pieter: Are you serious? You want to own a gun to take on the police? Please go & live in Syria.

Excellent article.

I can’t help thinking of a similar situation with dog owners versus people who are afraid of dogs. How often have you heard dog owners who let their dogs go unleashed but tell people that their dogs don’t bite?

I understand that every dog is presumed good until after the first bite.

How does this fit? Just another shade of grey in the overall continuum ?

We can argue that people don’t die from dog bites but the fear to others is the same.

You describe hunting as a nuisance that should be regulated. But is a federal or provincial law the ideal method of regulation? You seem to ignore the Coasian argument that the nuisance is reciprocal. Depending on the circumstances, it’s not obvious that an across the board regulation is the lowest cost means of addressing the problem. Perhaps the differences in rural and urban rules reflects an approximately optimal situation, insofar as the cost of not-hunting is higher for more of the rural population.